Friday, May 28, 2010

Friday, May 14, 2010

Special Town Meeting

Buffalo Bill’s son (minus hat), with florid face and cream-colored hair slicked back,

a country western legend, perhaps, or NASCAR granddad;

or a fur trapper woke up on the wrong side of the world

in the wrong time who, lacking a good saloon

where he could rest his mud-caked boots, drink rotgut and wait for a shootout,

came to town meeting, both barrels blazing against bureaucrats and taxes.

Fading purple banners drape the gym, heralding the school’s athletic heights.

At a humble angle, a basketball hoop glows above the aging moderator’s head.

Pony-tailed, neck-tied in leather jacket, he once ran wild on this shiny hardwood.

People here still remember when the gym erupted

the night he scored in overtime, or strained silently on folding chairs

to hear his narrator’s lines in “Our Town” on the dusty stage where he now lords.

The chair of the selectboard sits nearby,

who never commanded this space in high school; she sang off-key,

was too fat and couldn’t act, but now looks out imperiously.

Assessors, finance committee, and those paid to be here —

clerk, counsel, highway superintendent — ask for votes

in monotones to move money between accounts

and pay unemployment for the math teacher and librarian laid off last fall,

recorded for posterity and the brittle-boned:

videoed by a pale, redheaded teen directing his first shoot,

reported for the local daily by a bored transient doodling bleacher notes.

The rare townspeople who speak saunter Sammy Davis-like

to sing their fondled poems at open mike, and some make encores:

a solemn, short-haired woman quoting procedures,

a former selectman who endorses articles as though it's expected of him,

and big-bellied Buffalo Bill, opinions sharp as mutton-chop whiskers,

alleging backroom deals, irritated, still, by the paltry sum

the town gave him when it took his land for the sewer line a dozen years ago,

exercising his right to be heard, reading amendments in his slow, flourishing hand,

to put on the ballot or at least table the proposal to send out quarterly tax bills.

2008

Saturday, May 8, 2010

A religious experience

Last night I went to church. I’ll admit, I’m not nearly as devout now as I once was, but I’ve been going to the place off and on for more than 40 years, and I am still impressed by its spectacle and pageantry, and find its rituals familiar and comforting. Mine is one of those mega-churches—typically there are more than 35,000 of us in the stadium-like cathedral. It’s impressive and humbling to be in the middle of a crowd this size gathered together with a common purpose.

Last evening’s service began with a surprise, as three helmeted angels descended into the church from the sky, adorned in battle fatigues, with pink smoke trailing from their army boots, landing on the soft grass of the nave to the amazed cheers of the congregation. What a weird and riveting way to introduce the magic and the mystery of it all!

Generally, though, there are few surprises, and that’s what is so reassuring. The hymns, for example, never change, and always happen at the same point in the service, beginning with “Oh Say Can You See,” that soaring paean to bravery and patriotism, just before the priests enter.

Next, well into the service, comes that lilting call to community, “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” and then, an “inning” later (we divide our service into nine sections of varying lengths), the love song, “Sweet Caroline.” Until you have stood in the middle of 35,000 parishioners, drunk with adoration, standing, swaying, singing a cappella Neil Diamond’s hypnotic melody, “reaching out, touchin you, touchin me, Sweet Caroline, good times never seemed so good,” you can’t truly grasp the miracle of faith.

Okay, so this is not your stereotypical church. Take communion. We’ve substituted hot dogs and beer for bread and wine, with ample amounts of both, not just a wafer and a sip. We combine communion with the collection; as people approach the front of the long lines to receive their blessing, they give the acolytes a generous, prescribed offering. It’s a good thing we can economize in some places, as the service itself is rather long, generally more than three hours.

We emphasize rituals, but they are unique to our church. The Bouncing of the Beachballs; the Human Wave, in which the crowd participates in a moving display of praise, raising their arms heavenward in a spontaneous, yet choreographed, progression around the perimeter of the church; the prayer-like chants (they’re Latin, I think, or Greek: “lets goh red sochs” and “yan kees suc”); and strange characters like the possessed Kazoo Man, exhorting the crowd in his wild garb, a waist-length white robe with red piping, red strips of handkerchief drooping from either side of his navy hat, resembling a beagle’s floppy ears.

A giant video screen overlooking the church displays helpful insights about the service, as well as the Ten Commandments (Thou Shalt Not Smoke, We Shall Smite Thee if Thee Approach the Altar, Love Thy Neighbor, et cetera). And let’s face it, running a church of this size is not cheap, so its walls are covered with colorful reminders of our sponsors, Saint Gulf, Saint Volvo, Saint John Hancock, among others.

The youthful priests are many, but mute. They communicate with their bodies, from a distance, presenting a kind of visual hieroglyphics that unfolds like a play. It’s often slow and meditative, forcing you to focus on the smallest of acts. At other times the priests run around chasing the chalice, throwing it among themselves, batting at it with a short, thick staff.

There are rules and rituals for the priests, just as there are for us supplicants: chalk lines that, apparently, must be avoided at all costs, chess-like movements around a mystical, green-grass square, and choreographed exchanges at the altar between priests wearing different-colored robes (white or gray, usually, tight fitting to accommodate the motion, topped with a brimmed cap). Four priests in black direct the service, led by one wearing a kind of masked mitre, who plants himself at the head of the altar.

Their meaning is not always clear to the uninitiated, but there’s something universal and deeply satisfying about the priests’ motions. Their movements express what it means to be fully human, alive in a body, muscular, sensual, at once joyful and solemn, hard-working yet playful.

The service is as slow as the revolving earth, interspersed with cosmic bursts of activity, a metaphor for our own struggle with mortality. At its heart, the service evokes our highest aspirations to infuse our lives with passion, to sustain our capacity for joy, to not be defined by the imperatives of survival.

In my religion, you win some, you lose some. When the service is over, I can’t say I completely understand it. But I do know this: religion is not a game.

Thursday, May 6, 2010

The Great Saunter

We all had health concerns. M was recovering from two back surgeries less than a year earlier to remove cancerous cells in and around his spine. E had surgery on her Achilles tendon in December, and was in such discomfort two days before that she didn’t think she even would be able to start with us. B had to stop at mile 12 on our longest training walk due to knee pain. A knee injury I suffered in the fall seemed healed, but I had not put it to such a test.

Just four athletes in their 50s, beginning the 25th annual Great Saunter, a 32-mile walk around the perimeter of Manhattan, on May Day.

Happily, B, M, and I all completed the distance, and E felt fine for the first 10 miles (when she left for a family function). It took us 12 hours to complete the loop, beginning south of the Brooklyn Bridge at Fulton and South streets, up the west side along the Hudson River, across the island south of the Harlem River, and then back along the East River.

It was not as physically challenging as I had feared it might be, although my legs and feet were extremely sore the last couple of hours from standing so long. Three days later, I’m still hurting, though, from a matching pair of blisters on my toes, stiff legs (especially when I get up from sitting), and an aching right foot that forces me to limp.

More than 800 of us started out on a day warm enough for shorts and T-shirts, hot enough for sunscreen and extra fluids. I’m not sure how many finished—the ending was rather anticlimactic—but a number of walkers we saw several times on the west side were not to be seen beyond the George Washington Bridge.

The entire walk was low key. We wore numbers, but there was no start, per se; we simply noticed that some people had begun, so we decided to do the same. Along the route there were only a handful of volunteers, and we saw the same ones in several places. There were unmarked forks in the woods at the northern tip of Manhattan; fortunately we were near some experienced walkers who knew the right way. There was just one water stop along the entire 32 miles, despite the warm weather.

At the finish, we were simply handed a brownie, a T-shirt, and a blank certificate to which we added our name. The Great Saunter ended where it began, outside the Heartland Brewery, and I expected a party there Saturday night, but it was business as usual. B and I downed a pint of oatmeal stout and returned to our hotel room, and I hobbled out for some ibuprofen and food.

The walk, though, was glorious. Manhattan was ringed in green, and bubbling with children, on ball fields, in parks (we passed through more than 20 of them), running, walking, walking their dogs, and on bicycles, and there were many adult children as well doing the same activities.

The narrow strip of land between the Hudson River and West Side Highway was not only green, it was filled with well-tended flower gardens, with a lot less litter than I encounter on my walks in rural Massachusetts. M and B snapped away with their cameras. As we walked, we occasionally updated family and friends on our cell phones.

We walked at a moderate pace, and we seldom took breaks. We grabbed some sushi and juice from the Fairway Supermarket when E left us at 125th Street. We stopped beneath the George Washington Bridge to get a picture of the little red lighthouse on the Hudson’s eastern shore, and helped a bicyclist who had taken a bad spill trying to avoid a walker. On a shaded bench in Inwood Park, we ate a lunch of onion-olive focaccia, cheddar cheese, yogurt, and apple cider from a nearby farmers market. A young woman walker there told us she had signed up for a bicycle tour of New York’s five boroughs the very next day.

Turning south, we walked for 20 blocks or so in the middle of Harlem before angling over to the East River. To this point, we had mostly visited among ourselves, but now two middle-aged men and a woman veered off the main path, telling us that they were taking the “more interesting,” traditional route; the new one kept to the middle of the city for another mile-and-a-half, they said, to avoid some narrow stretches and street crossings. We decided to follow them.

The two men were from Poughkeepsie, where they work for IBM and belong to a walking club. This was their fourth Saunter. The woman lives in Brooklyn, and twice a week she walks the nine-and-a-half mile commute to and from her job as a bookkeeper on 57th Street.

I soon noticed a woman following us, and gradually drifted back and began a conversation. Maria was from Monterey, Mexico, and spoke limited English. She had become separated from four friends who began the walk with her; the five of them had traveled to New York to see “The Lion King” on Broadway the night before and then make the 32-mile walk. They were returning to Mexico Sunday.

Maria walked as if her feet were sore, so M offered to carry her backpack. She refused at first, but he persisted, and finally she relented. For the last third of the walk, M carried Maria’s backpack, though we were not always together—there were times when she was 100 yards or so in front of M, but she never once looked back. Her trust was gratifying.

The people we met were friendly, if a little bemused. Some older men by a street corner asked us how we liked Harlem River Park. When we answered that we had enjoyed it, one of them became animated and, introducing himself, said, “I started that park!”

Although the water looked murky, people were fishing all along the East River, poles bungeed to the metal railings above the water. We watched as one man reeled in an 18-inch eel, yelling, “I got a snake!” and warning the gathering crowd to not get too close because they bite and sting. “But they taste just like scallops,” he said.

We caught up to two nuns wearing beige-colored habits, one in sneakers. I turned to speak to them, expecting to see two older women. To my surprise, they were both in their 20s.

For the last few miles it was just B and I walking side by side, mostly in silence, with M and Maria a little behind. It was pleasant, but we were weary, and the remaining distance seemed elastic, expanding with every step. But it was an experience of New York unlike any I have ever had, or am likely to have.

The historic rivers and bridges; the ancient tulip trees and wooded paths juxtaposed with bustling sidewalks, cooking smells and traffic sounds; the mix of friends and friendly strangers; the exercise; even the exhaustion—all contributed to a unique perspective of this great city. Sore feet and all, I would walk it again.

Sunday, April 25, 2010

Splitting time

Splitting logs is payback, sending shockwaves through my body, transferring thin slabs of dense wood to reedy muscle. The two tall, red maples behind the garage were still alive; I made the decision to execute them because they were terminally ill and I chose not to invest the money necessary to make their last years comfortable.

They each must have been 75 years old—older than I am—and their thick trunks and wide canopies dominated their immediate landscape. These trees survived the insurance company with the son, now in his 70s, who threw wild parties as a teenager; the car mechanic with the daughter who loved horses; the cow rescued from the nearby swimming pool; the lady who died of cancer; the musical family with two young girls; and the couple who had legendary shouting matches; before us.

Now the lilacs can breathe, the hemlocks can branch out. No more dead or dying limbs, no more cables to keep them from splaying. For now, we will not replace them.

Their heavy remains will help warm our house or, more accurately, provide ambience, for the next several winters. The fireplace is inefficient for heating, but satisfying to watch, smell, and listen to, profound and primal as breaking ocean waves. A pile of dried logs licked by flames can be hypnotizing, calming, absorbing, regardless of season.

But now, the log lengths cover parts of the greening lawn, and they need to be split and stacked so they can dry enough to burn next fall. Sledge and maul come swinging down again and again with great force, though I am out of shape and have thin arms.

It is a familiar, fluid motion, like swinging a baseball bat, but vertically, and much heavier. Legs planted firmly, left arm extended, left hand gripping the wide base of the maul handle, I swing the maul up, slowly gaining speed. There is the briefest pause at the precise top of the upswing as my right hand grabs the handle above the left before exploding downward, powered by a sudden shift of weight through the fulcrum of the hips.

The result is either a dull, ringing thud, as less than an inch of the maul’s blade is buried in a thick log, or a satisfying crack, as two fireplace-size pieces fly in opposite directions. If the maul is wedged in the wood, I repeat the swing using the sledge, pounding the head of the maul like a pile driver until it cuts through.

I split a little more every day, until my shoulders tire. This is not a job that should be done when I am fatigued—I could take my leg off with a glancing blow. Such is the force that my energy must muster. Afterward, my upper body aches for hours, until a glass of white wine before dinner.

There are machines that can do this splitting, and the widest sections of the trunk may yet require one. But, like the Plains Indians that used every last shred of the buffalo they killed, I feel I must somehow acknowledge and take responsibility for the lives I took, utilizing all that I can from their corpses.

There’s the old adage about wood keeping you warm twice: once when you stack it, once when you burn it. While it doesn’t heat the house, the woodpile offers some security. If the power fails next winter, we could huddle around the fireplace and not freeze to death. Seeing three stacks of wood gaining height slowly from my effort feels akin to stocking the food pantry, a hedge against loss, unhurried and fragrant as rising bread dough.

The lily of the valley should recover. It has been covered for weeks with thick, fireplace-length logs. I rolled several logs away from the area, uncovering a number of pale, pink stalks tipped with yellow, trying to find the light. A few days later they had greened up, but I noticed a few more of the translucent spears poking up around the edges of the next log. I had to move half a dozen more logs to expose the full patch of lily of the valley.

I’m not sure what to do about the gnarled stumps. Striking them with the maul requires all my strength, just to crack a small wedge, and the effort makes my shoulders ring, vibrating my whole being, right down to my organs and bones. These trees will not go gently.

The largest log is about eighteen inches high and three feet in diameter. It will make a perfect table on the patio, but it weighs a ton and will have to be treated with some kind of preservative. I’ll need help to turn it on its side and roll it across the grass to its final resting place. It will be a lot more durable and attractive, though, than the chintzy, rusting table it will replace.

At my current pace, cleaning up the two trees will take until summer. I will be physically stronger from the work of splitting and stacking, with a deeper, visceral understanding of the land on which I live. The stumps and some sawdust will remain. It will be years before evidence of the trees will be gone, rotting into the ground, or turning to ash in my fireplace.

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

Fiddleheads

The fiddleheads are here! Like apple blossoms, they are appearing earlier than usual by a couple of weeks due to the unseasonably warm weather.

This poem originally appeared in the 2004 Berkshire Review.

Fiddleheads

Eight years after Yettie died

Rolando still sniffed the house

for boiled cabbage and bacon grease

lingering in the corners

he seldom swept or wiped.

He sat up sleepily,

gripping the bed on either side,

trying to recall her warmth and shape

lying next to him 51 years.

Scratching his head,

he looked down at his spotted legs

and was struck by how skinny he was,

although his belly sagged.

Today was May one.

He pulled himself up.

This was the day to get fiddleheads.

He dragged a comb across

his still thick, cream-colored hair

and threw his jacket on.

Rolando walked by their small stand

of tightly budded lilacs

on his way to the garage

and climbed into the car

he’d driven eleven years

that still ran well with minor repairs,

a cream-colored wagon like his hair,

and drove a mile or more

on dirt roads through new potato fields

until he came to a spot by the slow river

where the ferns annually unfolded.

Yettie wore a faded cotton dress

that seemed full of her life

like no other perfume.

She would set her line for yellow perch

while Rolando hunted through the wilds

of broken bottles and new growth until he

filled a bowl with the tender, tightly-wound scrolls.

They’d mix their catch that night,

fried with butter and a small onion

then simmered with milk into a thick stew

which they’d make three times

in the next two weeks

and then not at all for fifty-two.

Rolando turned the radio up

because who was he bothering

at this hour and in this place?

and inched along the road, avoiding the ruts,

thinking about the years now long ago

when he supervised two men in a greenhouse

growing half the pansies in western Massachusetts.

The moist greens and violets and golds

blossoming in a thousand rows

beneath acres of glass while outside it froze

kept his spirits up and his sleeves short

no matter how cold it got.

But the day picking fiddleheads

marked the change from plants sown indoors

to those that stirred from roots or seed

directly under wind and sun.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

Inconspicuous Consumption

When it comes to trash and recycling, I’ve always thought of myself as a conscientious consumer. But it’s hard not to make a mess.

I’ve been diligent about recycling for years, thanks in large part to having lived in communities that provide lots of recycling options, in a state with a bottle bill. But there is a large category of waste material about which I have been thoughtless until recently, and that has made me look more closely at my overall consumption of packaged goods.

My meals yesterday took a lot of protecting. At breakfast I emptied a plastic milk jug and opened the next, a cardboard carton with a plastic o-ring beneath its cap, protecting its spout. Both, at least, are recyclable.

I ate my cereal reading the Saturday newspaper, the thickest of the week, as it is always jammed with inserts. Yesterday’s had ten, plus Parade magazine and a television guide. All of them went directly to my recycling bin without a glance. The best argument I have heard yet for Kindles, iPads and online journalism is environmental, sparing not only thousands of trees on a daily basis, but the vast, energy- and resource-consuming infrastructure of press and ink, and delivery trucks fanning out to countless stores and home delivery.

The middle of the day was light on garbage, thanks in part to a five-hour walk on which we each consumed two granola bars wrapped in thin, mylar-like substances, which came packaged in a cardboard box. For lunch, I opened the plastic wrapper around a bar of cheddar cheese, and placed the unused portion in a plastic sandwich bag.

Supper was the killer. For a lasagna-style casserole, I used a plastic jar of tomato sauce; a plastic tub of cottage cheese with a protective plastic skin beneath its plastic cap; a plastic container of tofu; a plastic box of mushrooms wrapped in plastic; a head of cauliflower wrapped in plastic; spinach in a plastic bag; and pasta in a cardboard box with a cellophane window. The containers and box were recyclable and the bag reusable. The skin and wraps were not.

I finished a small, glass jar of capers and a plastic tub of black olives. I microwaved a plastic pouch of frozen peas (not recyclable) that came in a cardboard box (recyclable). We drank wine that came in a glass bottle (recyclable).

These are only the ingredients that, on this day, I used up and had to dispose of their containers. The jar of green olives, the cereal box, the plastic cups of blueberries and rice pudding will be recycled another day.

I’ve begun reusing aluminum foil, plastic cups and plastic bags until they are dirty or otherwise unsalvageable. Not so long ago, I would have thought of this modest effort as silly, unnecessary, or unsanitary, if I thought about it at all; quaint economies my grandparents made, persisting today only among the world’s poor. But more and more I am trying to model the behavior I expect of others, and I deplore the thoughtless trash that dots my landscape.

I am looking for ways to be fully engaged in the world I live in, and that means being accountable, not just abdicating responsibility to faceless governments and nations for the global problems to which I contribute. That requires me to look honestly at my own appetites, my role as a consumer in all its complexity.

In the final analysis, I can only change myself, do what is in front of me. I don’t know fully how using less can make a difference, but it is the surest weapon I have.

Tuesday, April 6, 2010

iPad, or pasta?

I was one of the last people in the western hemisphere to get a cell phone. I was always practical, waiting for other people to vet new technologies. More to the point, I resisted the marketing strains that seduce vacuous consumers to part with their money over anything labeled the Next Best Thing.

Yet there I was, at 8:55 a.m. on a Saturday in April, in line with 100 or more people outside the Apple store inside the Holyoke Mall, waiting to get my iPad. The marketers at Apple had not only convinced me to pre-order, they had threatened that I would forfeit the chance to get my new machine if I were not there between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m.!

It was an impressive display of mass marketing. There was free Starbucks coffee and bottled water for people in line—two lines, actually: one for those lucky ones like me who had pre-ordered, one for those hapless losers who stood enviously waiting to order, hoping for the opportunity to spend their money on the cool promise of the much-hyped machine.

There was irony galore. The line was opposite a Borders bookstore, and security staff had to instruct us several times to move away from Borders’ doors. The teenage boy behind me uttered comments like “I’ll never buy another book again.”

I called two friends to help document this historic moment. The first was duly impressed, but the other was too sleepy to appreciate it. There was no common denominator to my compadres in line, no universal demographic—young and old, male and female, geek and non-geek all gathered together to be the first ones on their block to bring home the latest from Jobs and Co.

It took 45 minutes for me to reach the head of the line. A pleasant young woman in a blue, short-sleeved crew-shirt crossed off my name from a plastic clipboard and announced through her headset that “Russell” was ready. I was then allowed to enter the store. I was greeted by my first name by more young people wearing blue crew-shirts. This cutting-edge technology was uniform, but with a human face!

The rest was anticlimactic. I was handed my machine, paid for it and left in a matter of moments, without fanfare. But like Woodstock, years from now I can say I was there.

I can’t yet tell you much about the new machine. It looks like fun—that is a given, I suppose. An iPhone on steroids, and probably much, much more, depending on how much time and money I invest in it, adding applications to the basic package that came with the machine (part of the Apple master plan).

But whatever it is, I will know about it now, not a year from now, or by reading about it. For the moment, at least, I am on the cyber frontier.

It is far too early to know if the iPad will deliver on its promise to transform our communication lives, or to speculate over whether it represents our doom, or salvation. But the people in line, including me, were betting on the latter. Driving this merchandising machine is hope that technology is a force for good, and can lead us through myriad challenges.

A week earlier, while walking with my housemate and our dog, we passed a yard sale, unattended and unattractive. But there, amid a blanket of forgettable items, was a stolid Royal typewriter.

I have not owned a typewriter since the early 1980s, when a student borrowed my portable electronic model and never returned it. That typewriter was a gift meant to encourage me to write, but it was light enough that it often jumped when I hit the carriage return, and it became obsolete when I bought my first IBM computer.

Since then, though, I have often wanted a typewriter in my repertoire. Its unique quirkiness is compelling: the smell of oil and inky ribbon; the sound of the bell announcing the end of a line, and the hand-crank of the carriage return; and its heavy bulk and unyielding keyboard that requires muscular finger strokes. Faster and more flexible than hand-writing, the typewriter nonetheless forces the user to think before putting words to paper, lest the letter, essay or narrative has to be typed all over again.

The Royal on the pavement was dusty, but otherwise appeared in great shape. I tested it, and it worked. A man in a woven navy cap, plaid shirt and chipped tooth came out and made light conversation, telling us a slow, sad story of a wounded heron. We never exchanged names. The heron finally breathing its last breath, I asked him what he wanted for the typewriter.

He said his mother owned it, and she was moving to Arizona. He put the question back to me: what did I think it was worth?

I was thinking $20, but I didn’t say it, instead batting the question back to him, telling him I had no idea, and what did he want for it?

He paused in the manner of any good salesperson. “Well,” he began slowly, hands in pockets, “I have to think it’s worth …” here he paused again, hand to stubbled chin, “… at least a buck,” looking up at me hopefully over his wire-frame glasses.

I tried not to accept too quickly, but paid him the dollar. He was glad to get rid of the Royal. One less thing to cart away, and a heavy one at that. Said his mother probably hadn’t touched it for years. I believed him, doomed heron and all.

The ancient typewriter, despite its weight, is in some respects like the sleek iPad. I can’t yet say exactly how I will use either of them, but both feed my desire to communicate with others. It feels a little like opening my pantry door in January and taking comfort at the canned goods and boxes filling the shelves.

If the power goes out, I’m protected. In any event, I have choices. My larder is well stocked, with dried mushrooms and cornichons from France and staples like pasta. No storm, no wind or snowdrift, can leave me hungry, or isolated, for long.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Fighting Fear

There is no debate over healthcare. Consider:

- Everyone wants healthcare for themselves (especially when they become ill or injured).

- Selfish as we Americans sometimes can be, we don’t really want our friends or neighbors to go without healthcare, either (Immigrants? Well, that’s another story.).

- No one believes the status quo is working, or sustainable.

- Flawed as the current healthcare bill may be, the opposition presents no alternative (After half a century of inaction, “starting over” is indefensible, and it does not constitute a contrasting program.).

- By their own admission, the people who most passionately oppose the healthcare bill don’t really know what is in it.

The small business owner from Utah who traveled to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s home in Nevada to protest passage of the healthcare bill, one of several opponents interviewed on NPR, said she feared the provisions of the bill would force her out of business by making her buy health insurance for her employees. Told by the reporter that the bill includes subsidies and tax credits for businesses like hers, the woman scoffed, saying that “no one” knows what is in the bill. Presumably, she includes herself in that statement.

If her business was a profitable one, if she felt secure about the future demand for her product or service, I doubt that she would spend the time and money to fight legislation she knows nothing about.

This is about fear, pure and simple.

Fear of a world that is changing too fast.

Fear of a black president, and the larger truth he represents (as writer James Baldwin uttered 30 years ago, “The world will never be white again.”).

Fear of an economy spinning beyond our control, of losing our national superiority and our material ease.

Fear of the transition from fossil fuels to something more sustainable, as yet unknown, of becoming casualties of the slow, uncertain and painful process of having to retool major industries like automobiles and energy.

Fear of being held accountable for our nation’s past sins against nature.

Fear of wars waged in two places that lack shape or common purpose and drain our nation’s resources like twin black holes.

Fear of not fighting these battles, powerless against an evasive, unseen enemy.

Fear of a bomb going off in our midst.

Change, we know, is inevitable. We cannot still our brains, even if we wanted to. As a species, we are in perpetual motion, relentless as the passage of time, and subject to its rules. That’s why, thousands of years after dwelling in caves and living from meal to meal, we take collective action to feed and clothe ourselves, to travel between destinations, to gain knowledge and new skills, to defend and protect ourselves, and now, to take care of each other when we are stricken by injury or disease.

No amount of fear can change this. But fear can wreak havoc along the way.

Sunday, March 28, 2010

All arms and legs

Running (or throwing or jumping) and painting (or drawing or carving) are both physical, solitary acts. We may run in a pack or paint in a class, but the experience is largely our own; to the runner and the painter, teamwork and collaboration are attainable, but they begin as largely abstract concepts.

Unlike team sports such as basketball or crew, the challenge of running is intensely personal. We are testing our physical limits, finding our threshold of maximum exertion, trying to hold concentration and relaxation together in perfect balance under intense conditions. It is a supreme experience of energy, powerful, and extremely difficult to sustain.

Unlike video or film, painting, too, resists collaboration. Even the act of writing, while largely solitary, lends itself to editorial input from others, and the words on the page can be changed at any time, and then changed back again. Painting is less easy to revise.

To either run or paint well requires a seeming paradox: discipline and control to produce fluidity and freedom. Harnessing energy to release it.

Running and painting are both sensual acts, but running is macro and external, painting micro and internal. Running engages all of the senses, a rich immersion in the physical world. But the sensuality is impersonal. Runners—and more generally, athletes—are to be seen, not touched.

Athletes are their own paintings, perpetual-motion sculptures. Runners are physically fit, and good running form is graceful, pleasing to the eye. We run in nothing but shorts, exposing our thin arms and muscular thighs, but the pleasure is distant and ephemeral, not sexual. Like the painting in the museum, the runner is to be admired from afar, not felt.

Painting, by contrast, is intimate, even erotic, soft and fluid, curvaceous, filled with color and light. The motions are smaller than running, though the experience can be as exhausting and intense, as the flow of energy through the arm is equally strong as through the legs.

Unlike running, when painting is done, something remains; energy is fixed. Running is like firewood, burning brightly and generating great heat for a limited time; painting is like the steel forged in the fire. Neither, of course, is truly permanent, but painting leaves longer traces.

My experience of energy is passing from athletics to art. Muscle strains and knee pain have prevented me from sustained or intense training in the past year or so. I have slowly come to accept the reality that I will have to be a more casual athlete from now on, recreational rather than competitive, running for my general mental and physical health, not as a primary means of self-expression. I have already given up sports like basketball and softball for fear of injury, as I feel neither capable nor interested in slowing down my approach. The game remains, but not the same force of energy.

At the heart of my love for athletics has been my experience of energy. It borders on the electric. I almost become another person when I step across the foul line onto the softball field or walk onto the basketball court, hyper-charged with an energy that feels as if it originates somewhere other than in myself.

But while my legs are no longer capable of channeling energy in the same way, the flow remains, entering my body involuntarily and eventually needing to find a way out. Fortunately, I can engage my arms, hands and wrists in the act of painting, where I can process the energy, energy which I am drawn to but do not fully comprehend.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Twilight Zone

For many years, with the aid of Vinny, a gentle but persistent Siamese cat, I would wake up sometime between 5 a.m. and 6 a.m., roll out of bed and go for an hour-long walk (after feeding Vinny). I would leave before breakfast, and usually before coffee or tea — just lace my shoes, throw on coat and hat (depending on time of year), and go, jerked like a water skier behind my motorboat black lab, Mickey.

In the fields and off leash, Mickey’s concentration on tennis ball or stick was absolute, and I could relax (one morning I spotted a bear about fifty yards away but Mickey was, thankfully, oblivious, flipping a stick in the air with his nose and catching it). I was self-employed during these years, so even in the darkest days of winter, I could leave as late as seven o’clock and still have plenty of time to get ready to begin work at nine. The walks gave me ample time to appreciate my surroundings, get my bearings and contemplate the day.

I love the morning; no matter how much or how little sleep I have had, I am at my freshest, and there are few distractions during these early hours. It is solitary, quiet, and there are often spectacular sunrises that otherwise would go unnoticed. When I returned home I felt as if I had earned my breakfast, and the exercise and fresh air laid a solid foundation for whatever else befell me during the day. No matter how stressful work or life might get, I had already done something good for myself. I even got used to the cold during winter, shrugging it off, even embracing it, following Mickey’s example.

Now my rhythm has changed, and I walk late afternoons into evening. I still get up early, but spend the time writing, reading or doing household chores rather than walking. I now put on my walking shoes when I get home from my day job, around five, and I have come to crave the slow, sensual transition from sunset to twilight to stars.

I was a late convert to digital photography, for reasons that seem foolish now, if I even can recall them. Something about the added degree of difficulty associated with film — digital looked too easy (never mind that traditional photography is a facile, mechanical shorthand for drawing what we see). In any event, I held out for a long time, with a vague, if naïve, belief that it had something to do with artistic integrity.

Silly me. During these twilight walks, I can take photographs without a tripod or flash that would be impossible using film. A whole new world has opened before me, expanding, not compromising, my experience of taking pictures. It has been several years now since I have shot with film, and I am still a neophyte with digital. But these twilight walks encourage me to push the boundaries of what can be captured on camera.

Today I began my walk shooting tobacco barns in slanted, late-afternoon light, then gingerly crossed a narrow slat bridge resting on the surface of the swollen Mill River. I arrived at the Connecticut when its expanse was a shifting blend of blues and apricot. The sun had disappeared; it was twilight, but I kept shooting. The light was so subtle and rich that it felt like time was suspended, or that it filled the air rather than simply passed through it. The light lacked a specific value, but infused everything in sight with a dense, yet transparent, hue.

The camera flash had still not gone off and I had nothing to lose (more advantages of digital—low light, low cost and instant access), so I tried the moon next, a thin crescent pointing skyward, poised over the silhouette of a tobacco barn that jutted above an orange horizon seeping above the tree line. The pictures might not come out, but who cares? They might communicate the moment, if not the literal image. When we walk, after all, things look blurred at times as our head moves in opposition to our feet at varying speeds on uneven surfaces. So what exactly is literal, anyway?

No matter which way I walk to the river, the return from my walk brings me to town, where pedestrian electric light contrasts with moon and stars: the ghost-like reflections of television sets undulating on walls; the steady red eye beaming from a small metal box affixed to a telephone pole; warm, incandescent lights of kitchens and dining rooms as people sit down to eat. At this hour, I am straddling worlds — the semi-wilderness from which I return, and the human habitation at the end of my journey. I feel kinship with both; a double dose of longing, and belonging.

Once back on Maple Street, I heard a car slow down and stop behind me. It seemed an odd place to pull over, between driveways, but I just kept walking, not bothering to look around.

A minute later, the car went slowly past me, and once again came to a stop by the side of the road. Perhaps the driver was lost and, having searched a map unsuccessfully a moment ago, was going to ask me for directions. Or perhaps, I thought, remembering being hassled at night in small towns sometimes as a teenager, someone was going to give me hard time. Either way, I didn’t feel much like talking.

The door opened, and the driver slowly got out as I neared the car. But instead of looking toward me, he turned and faced the direction I was going, took something from his coat pocket, and pointed it at the sky.

It was a digital camera. He, too, was still shooting, aiming to capture the sliver of a moon in the deepening indigo evening. I opened my mouth to offer encouragement, but closed it before speaking. A picture says a thousand words.

Monday, March 15, 2010

Mud Season Redux

It’s quarter of one on a Saturday afternoon in March, and I’m ready for a nap. I’ve been up since five, as our still-young dog, Molly, apparently miscalculated and had to get up to pee. By the time I am dressed and stand with her outside, I no longer feel sleepy, so I stay awake, but it is catching up with me now. With Molly, too—she is curled up on the sofa fast asleep—and my housemate, who has a bad cold and, after a restless night, has wisely gone back to bed.

I’ve been paying bills, which always leaves me feeling stressed out, even after a good night’s rest. It’s vaguely satisfying to know that everyone has been paid, but the effort leaves my head spinning. It’s time to lie down or take a walk.

With temperatures in the low 40s, gusty winds and gray skies, it seems like a no-brainer: take the nap. But the weekend forecast calls for heavy rain, and it is only sprinkling now. Between this morning’s rain and what is predicted, this may be my best window of opportunity. That angelic-looking dog will be totally wired when she wakes up in a few hours if she does not get some exercise. So I chose to walk.

In certain respects the landscape now resembles the starkness of the Cape Cod dunes. At first you feel as if you are in a world of a few broad, monochromatic bands. But once you have been there awhile, your eyes adjust like night vision, and you see details within each band you missed upon first or second glance.

At a distance, it looks as if a fine red scrim drapes the leafless trees. The blue foothills of the Berkshires are shades of purple and slate gray. The dead grasses covering the fields, dull and uninspiring in sunlight, are a vivid gold, as an ember glows brightly before expiring.

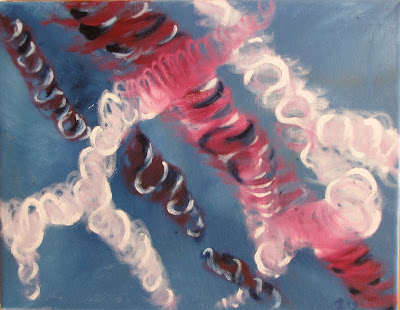

Along the perimeter of the fields, a profusion of maroon and pink blackberry canes arch gracefully in every direction, inspiration and a crude model, perhaps, for the invention of fireworks. I have no doubt that the abstract shapes and lines I paint have their origin in nature.

Rain at this time of year does a better job at coaxing green from the earth than the sun—it always looks brighter after a spring shower. Today is no exception. The fields are noticeably greener than during the previous week of sunny weather.

The earth is deceptively solid in places, like a breached whale before it descends back into the murky depths. It won’t last. Before the end of the walk, some of last week’s puddles have already reappeared and, if the forecast holds true, Monday the land will be submerged again.

While the whale-backed field will temporarily disappear, the flotsam remains. A sea of beer, bottled water and Gatorade is consumed in and around these fields, and their detritus is everywhere. In addition to the cans and bottles, there is industrial waste, from tires to plastic jugs to rusting metal. There are abandoned mattresses, and appliances: a refrigerator, an air conditioner, a toxic computer left, not to rot—they are made of too much plastic and non-biodegradable material—but to permanently (or as close as we know it) scar the landscape.

Many of us experience odd moments when we feel like aliens. My friend Peter, a casual sports fan, tried to make conversation at a Super Bowl party a few years ago, in between plays and during the ads. The dismayed gathering mostly ignored him, and at that instant, he knew he was an alien. There are many places this awareness can happen in modern America (like fast food restaurants, or watching television).

That’s how I experience this garbage. I just don’t get it. It’s not judgmental; I simply cannot understand why anyone would be so careless or indifferent as to violate the beauty of this space. This cavalier attitude is foreign, er, alien to me.

But the world here is too big for the trash to ruin my experience. Lately, my partner and I have become members of a silent resistance, bringing trash bags with us on many of these walks and hauling out as much of this junk as we can carry. It may not amount to much, but it feels better to be engaged than passive

The elements, though, are too daunting for that today.

I reach the end of the dike and pause at the river before turning toward home. The wind now is in my face, and the rain has picked up, needling my cheeks. I have to keep my head down and hold on to my hat. Before long water is dripping from its brim, my glasses are spotted with raindrops, and my hands are red with cold. The wind in my ears is a constant roar; when it briefly lets up now and then it merely allows me to hear it blowing further away, through the trees or across the river.

Molly is unaffected. To her, this could be the most beautiful day of the year. She runs around in mad circles, chases the birds wherever they land, sniffs everything in sight. I see a muskrat swimming in the Mill River, am startled by the brightness of a bluebird. There are deer prints in the mud near the river. Three stoic Hereford cattle lie chewing their cuds, two beneath a lean-to, one in the rain. Until I am back in town, these are the only living creatures I encounter.

The rain lets up once I am on Main Street. We walk swiftly home. Once there, I take a long nap.